16th October 2018

What is Whisky Made From?

Beer. At least that’s the short answer.

Much like brandy is made by distilling wine, whisky is made by distilling beer, or at least something very close to beer – I wouldn’t recommend drinking a pint of it.

The longer answer, which is still fairly short is that whisky is made from cereals (grains such as barley, corn and rye – not Cornflakes). These grains are combined with water to produce a sugary mixture known as wort, which is then fermented to produce an alcoholic liquid (similar to beer) called wash. The wash is distilled to increase the alcohol content, while reducing unwanted and concentrating desired aromas before being aged, or matured, in wooden casks.

So what is malt whisky?

Malt whisky is made using 100% malted barley. The malt whisky production process entails the following steps:

Malt whisky is made using 100% malted barley. The malt whisky production process entails the following steps:

- Malting barley

- Mashing and fermentation

- Distillation

- Maturing and bottling

A single malt whisky is a malt whisky produced by a single distillery, i.e. not a blend of several distilleries’ malts. A single malt however does not have to come from a single barrel (which would be a single cask malt whisky) but is commonly a mix of several casks from the distillery, allowing the manufacturers to achieve a higher level of consistency in their product despite small variations between batches and casks.

And that’s all there is to it?

Not quite. Each whisky style or whisky producing region has their own set of regulations dictating when the distilled spirit is allowed to be labelled as whisky. For example, the Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009 set forth that “Scotch Whisky” means a whisky:

- produced entirely in Scotland;

- that has been distilled at an alcoholic strength by volume of less than 94.8 per cent so that the distillate has an aroma and taste derived from the raw materials used in its production;

- that has been matured entirely in an excise warehouse or a permitted place in Scotland in oak casks of a capacity not exceeding 700 litres for a period of not less than three years;

- to which no substance has been added except water and/or plain caramel colouring; and

- that is bottled at a minimum alcoholic strength by volume of 40%.

We will cover the regulations of each style/region (Bourbon Whiskey, Rye Whisky, Japanese Whisky) when we look at each of these whiskies in more detail in future articles.

Want to learn more about whisky production?

Take a look at the first step in the production process: Malting barley

You might also like:

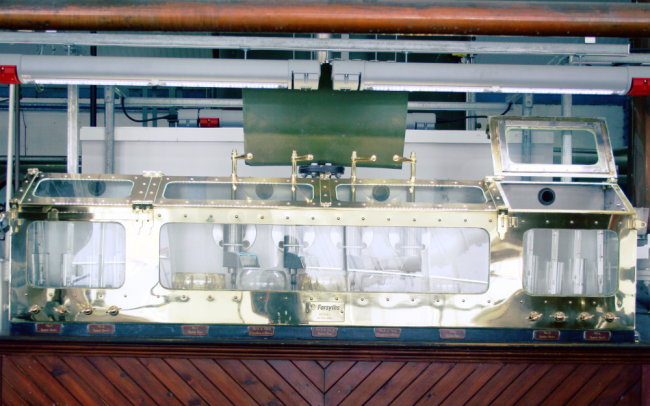

The stills in which single malt Scotch whisky is produced are, by law, made from copper. They consist of a large pot base with a tall, thin neck (known as a “swan neck”), which ends in an angled turn into a pipe called a lyne arm. This pipe is connected to a condenser which will cool the vapours coming off the still back into liquid form. The liquid coming off the stills then flows through a receiving vessel called a spirit safe. This is a locked glass box where the stillman can check the spirit and decide when to start collecting the liquid that will become whisky. The spirit safe is kept locked by the local excise official to prevent alcohol from being siphoned off before it can be measured for tax purposes. The first still, into which the wash is filled, is called the wash still. When heated, the ethanol, as well as various compounds, will begin to vaporise and rise in the still. Much of the vapour will condense on the sides of the still and fall back into the pot. This reflux ensures that only the lighter, desirable compounds reach the top of the still. The copper in the stills also helps to strip away the heavier compounds, such as sulphur, ensuring a lighter spirit. Once the vapour has made it around the head and into the lyne arm, it reaches the condensors. Here cold water flows along the sides of the pipes to cool the vapour back into liquid form. The liquid, now called low wines passes through the spirit safe and is collected in the low wines receiver. The liquid coming off the still first is higher in alcohol (roughly 45% ABV); as the distillation progresses the alcohol content falls. When the alcohol content of the low wines coming off the still reaches around 1% the distillation is deemed complete. The collected low wines will have be approximately 25% ABV. The second distillation takes place in the spirit still. It is similar to the first, however the resulting liquid is separated into three “cuts”: heads, hearts and tails. The heads, also called foreshots, are the first runnings of the spirit still. They contain all of the lighter compounds that vaporise first, including volatile and aromatic compounds such as ethyl acetate. These are not deemed worthy of collection and are rerouted via the spirit safe back to the low wines receiver. They will be distilled again with the next batch. After approximately 10 – 30 minutes, once the alcohol content has fallen to roughly 75% ABV, the stillman will turn a handle in the spirit safe and begin collecting the hearts. The hearts, also called the middle cut, contain all of the desirable flavours and aroma compounds. This liquid will be collected in the spirit receiver and will later, after maturation, become whisky. For now though it is called new make spirit. The choice of when to begin and stop collecting the hearts has a major impact on the level of compounds in the final spirit. Therefore this decision has a significant effect on the final character and is a major contributor to the differences between whiskies from separate distilleries. Another contributing factor to the differences between distilleries is the shape of the still and the angle of the lyne arm. Shape and height both influence the level of copper contact and reflux. Taller stills with upward reaching lyne arms generally result in lighter whiskies. Collection of the new spirit lasts roughly 3 hours, when the alcohol content falls to roughly 60% ABV, before the tails begin to run off the still. The tails, also called the feints, contain all of the heavier compounds, such as fusel oils, that are not desirable in the spirit. The stillman will again turn the handle on the spirit safe and redirect the tails to the low wines receiver. Again these will be distilled in the next run. The collected new make will now be transferred to casks for maturation. Take a look at the next step in the production process: Maturation and Bottling.

The stills in which single malt Scotch whisky is produced are, by law, made from copper. They consist of a large pot base with a tall, thin neck (known as a “swan neck”), which ends in an angled turn into a pipe called a lyne arm. This pipe is connected to a condenser which will cool the vapours coming off the still back into liquid form. The liquid coming off the stills then flows through a receiving vessel called a spirit safe. This is a locked glass box where the stillman can check the spirit and decide when to start collecting the liquid that will become whisky. The spirit safe is kept locked by the local excise official to prevent alcohol from being siphoned off before it can be measured for tax purposes. The first still, into which the wash is filled, is called the wash still. When heated, the ethanol, as well as various compounds, will begin to vaporise and rise in the still. Much of the vapour will condense on the sides of the still and fall back into the pot. This reflux ensures that only the lighter, desirable compounds reach the top of the still. The copper in the stills also helps to strip away the heavier compounds, such as sulphur, ensuring a lighter spirit. Once the vapour has made it around the head and into the lyne arm, it reaches the condensors. Here cold water flows along the sides of the pipes to cool the vapour back into liquid form. The liquid, now called low wines passes through the spirit safe and is collected in the low wines receiver. The liquid coming off the still first is higher in alcohol (roughly 45% ABV); as the distillation progresses the alcohol content falls. When the alcohol content of the low wines coming off the still reaches around 1% the distillation is deemed complete. The collected low wines will have be approximately 25% ABV. The second distillation takes place in the spirit still. It is similar to the first, however the resulting liquid is separated into three “cuts”: heads, hearts and tails. The heads, also called foreshots, are the first runnings of the spirit still. They contain all of the lighter compounds that vaporise first, including volatile and aromatic compounds such as ethyl acetate. These are not deemed worthy of collection and are rerouted via the spirit safe back to the low wines receiver. They will be distilled again with the next batch. After approximately 10 – 30 minutes, once the alcohol content has fallen to roughly 75% ABV, the stillman will turn a handle in the spirit safe and begin collecting the hearts. The hearts, also called the middle cut, contain all of the desirable flavours and aroma compounds. This liquid will be collected in the spirit receiver and will later, after maturation, become whisky. For now though it is called new make spirit. The choice of when to begin and stop collecting the hearts has a major impact on the level of compounds in the final spirit. Therefore this decision has a significant effect on the final character and is a major contributor to the differences between whiskies from separate distilleries. Another contributing factor to the differences between distilleries is the shape of the still and the angle of the lyne arm. Shape and height both influence the level of copper contact and reflux. Taller stills with upward reaching lyne arms generally result in lighter whiskies. Collection of the new spirit lasts roughly 3 hours, when the alcohol content falls to roughly 60% ABV, before the tails begin to run off the still. The tails, also called the feints, contain all of the heavier compounds, such as fusel oils, that are not desirable in the spirit. The stillman will again turn the handle on the spirit safe and redirect the tails to the low wines receiver. Again these will be distilled in the next run. The collected new make will now be transferred to casks for maturation. Take a look at the next step in the production process: Maturation and Bottling.

As mentioned above, the germination process has to be stopped before the embryo consumes the sugars. This is done in the kiln – the chimney of which is the large pagoda roof featured on the majority of distilleries – by blowing hot air through the grains. It is at this stage that many whiskies pick up their smoky character. Prior to drying with air the green malt is introduced to smoke by lighting a peat fire below the kiln. Back in the day many distilleries would not have had access to other heating materials such as coal or wood and will have used what natural resources were available for drying the malt. In the case of many areas in Scotland, especially Islay, peat was an abundant material. Even after the introduction of better heating sources the practice continued due to the distinctive character it lends to the whisky. By adjusting the level of air flow and temperature, malts of different flavours and colours can be produced. The moisture content of the dried malt is roughly 3 – 6%. The malt is then put through a deculmer machine to remove the tiny rootlets that emerged during germination before being stored ready for the next step in production: Mashing and Fermentation. Take a look at the next step in the production process: Mashing and Fermentation

As mentioned above, the germination process has to be stopped before the embryo consumes the sugars. This is done in the kiln – the chimney of which is the large pagoda roof featured on the majority of distilleries – by blowing hot air through the grains. It is at this stage that many whiskies pick up their smoky character. Prior to drying with air the green malt is introduced to smoke by lighting a peat fire below the kiln. Back in the day many distilleries would not have had access to other heating materials such as coal or wood and will have used what natural resources were available for drying the malt. In the case of many areas in Scotland, especially Islay, peat was an abundant material. Even after the introduction of better heating sources the practice continued due to the distinctive character it lends to the whisky. By adjusting the level of air flow and temperature, malts of different flavours and colours can be produced. The moisture content of the dried malt is roughly 3 – 6%. The malt is then put through a deculmer machine to remove the tiny rootlets that emerged during germination before being stored ready for the next step in production: Mashing and Fermentation. Take a look at the next step in the production process: Mashing and Fermentation